Stanley Moody, L.P.N., administers a medication injection in the van, which is being tested as part of the NIH HEAL Initiative research project. Credit: Kevin R. Wenzel, Ph.D., Mountain Manor Treatment Center

In the opioid crisis, young people face higher risks at every turn. They are often first exposed to opioids as teens and young adults, when they are especially prone to misuse and addiction. A 2019 study found that 57 percent of youth between the ages of 12 and 25 who reported misusing prescription opioids got them from friends or relatives, and 25 percent from healthcare providers.

Marc Fishman, M.D., medical director of Maryland Treatment Centers, knows this only too well. He’s been working with young people with opioid use disorder (OUD) in Baltimore for nearly two decades and seen firsthand how the normal development of a young mind, not yet fully mature, but no longer a child’s, can contribute to opioid misuse and OUD.

Now, with support from the NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, his team is testing variations of the Youth Opioid Recovery Support (YORS) intervention to help young people with OUD continue medication treatment and stay in recovery.

The NIH HEAL Initiative is funding several research projects examining behavioral interventions that might improve outcomes of medication-based treatment. Fishman’s project is administered by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Young adults between the ages of 18 and 26 are at greater risk for misusing opioids and developing OUD than other age groups. Studies have shown they also are very likely to stop medication treatment for OUD, often within a few weeks, putting them at high risk for relapse and overdose.

Fishman, principal investigator for the project, and his team are seeking ways to overcome the barriers that keep young adults from continuing medication-based treatment for OUD. The project is based at the Mountain Manor Treatment Center for young adults in Baltimore.

A growing problem locally and nationally

The opioid crisis is a now national epidemic, but Baltimore has had significant opioid problems since the 1970s, when heroin was the main opioid afflicting the city.

“That background of heroin use has remained, but now we see layer on layer, wave on wave of opioid addiction with different features,” Fishman said. “With the current crisis, we saw initiation of OUD through misuse of prescription opioids and widespread use in suburban and rural areas.” Fishman is also alarmed by the flood of synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which are highly potent and pose a great risk of overdose and death.

Getting young people into treatment is a critical need, but treatment can be challenging for several reasons, said Fishman.

“Young adults feel grown up before they really are. They are testing out independent living strategies, but their developmental immaturity makes it very difficult for them to start and stick with treatment for OUD,” he explained. “They also believe they’re invincible, and they live in the moment. They take risks. In addition, young adults don’t like to think of themselves as being sick, and this means it is often hard for them to accept treatment and stick with it.”

When a person is undergoing detoxification in a treatment facility, they may receive the first injection of an extended-release OUD medication or start taking an oral one. They are also referred for continuing care and counseling after they leave the facility.

Unfortunately, once people leave the treatment center, most face many obstacles to continue medication. Studies have found that only half of patients who start oral naltrexone remain in treatment six weeks later and only 15 percent are still on it after six months. Most patients who receive the injectable version don’t even return to their health care provider for a second shot.

Alongside the psychological factors related to immaturity, young adults face other hurdles – from lack of transportation to lack of time. Going to a clinic for regular injections can be a challenge for those who are in school or have jobs. Often, parents and others don’t understand what’s involved in medication treatment and how effective it can be. Personal relationships may be broken or dysfunctional because of OUD, leaving people who have OUD with scant social or emotional support. Stigma related to addiction and treatment is common.

A personal crisis, however, such as becoming homeless or going through detoxification, can open a “nanosecond” of opportunity when a young adult is motivated to get help with treatment — and that’s when the team have a chance to intervene, Fishman explained.

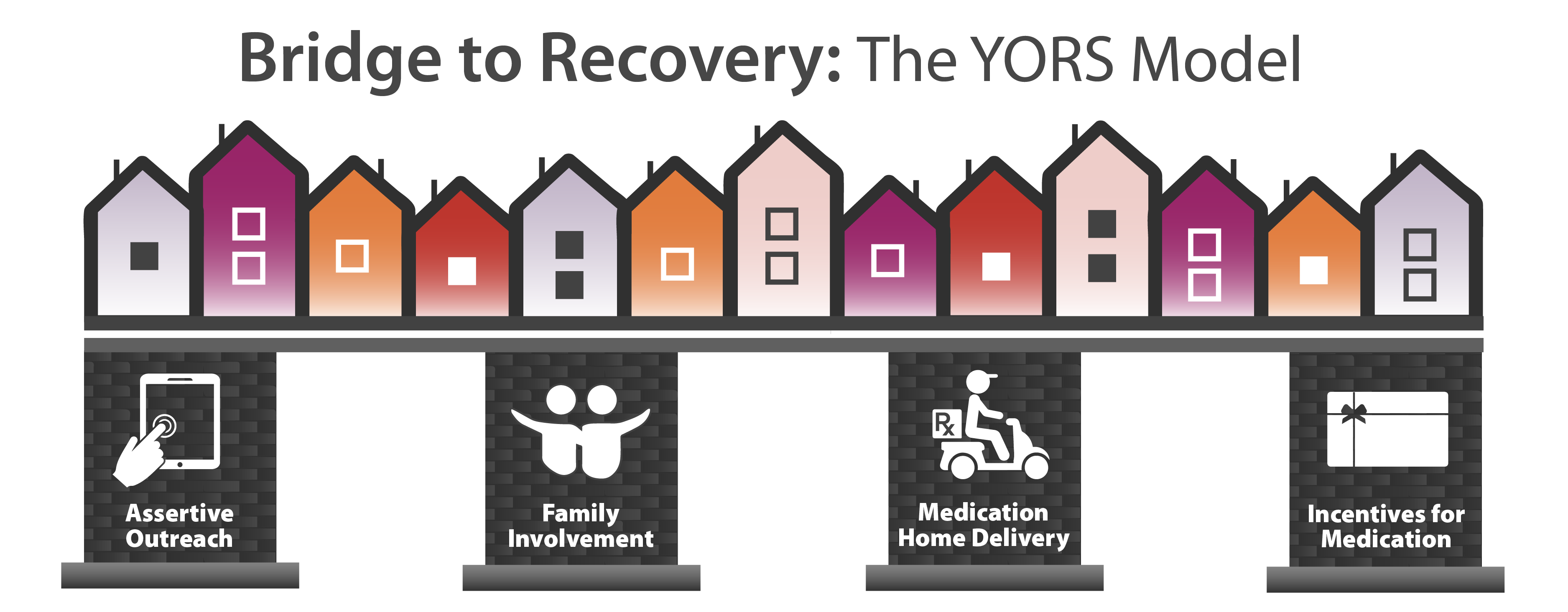

The Youth Opioid Recovery Support model.

Credit: NIH HEAL Initiative

Overcoming barriers with an innovative support system for OUD treatment

Fishman and his colleagues “stole shamelessly from the playbook of successful behavioral interventions” as they developed the Youth Opioid Recovery Support model, he said. The intervention consists of four supports – assertive outreach, family involvement, medication home delivery, and incentives for medication compliance – designed to overcome these barriers to continuing medication treatment for OUD.

The study team uses assertive outreach to encourage participants to receive OUD medications as prescribed and engage participants and family members via text messaging, phone calls, Facebook Messenger, email, and postal mail. Research participants agree to involve a parent, another family member, or a significant other to help create a treatment plan and encourage the participant to continue his or her medication regimen. With home delivery, long-acting OUD medication can be given in a person’s home, work, a clinic, or elsewhere. Finally, study participants receive financial incentives in the form of gift cards when they receive a dose of OUD medication.

A pilot test of the model at Mountain Manor yielded impressive results. The research team randomly assigned 40 young adults to one of two groups. One group participated in the full intervention, and the control group received the clinic’s usual treatment for OUD (one dose of a long-acting OUD medication and referrals for continued treatment). After six months, 19 of the 20 (95 percent) participants in the control group had relapsed to regular opioid use, but only 11 of the 18 (60 percent) intervention participants had relapsed. In addition, participants in the intervention group had received an average of more than four monthly doses of medication during the study; participants in the control group received less than one dose on average.

Refining the model to get better results

The promising results of the pilot led to the current 2-year project funded by the NIH HEAL Initiative, which is testing various tweaks of the YORS model to see if they help young adults continue medication treatment.

“As successful as the combined intervention model was, more than half of the pilot-test participants still relapsed,” Fishman explained. “So, for the first one or two years of the HEAL project, we are refining and improving the YORS intervention based on lessons learned from the pilot.”

To get feedback and ideas for improving the model, the study team brought together focus groups of pilot-study participants and their family members, clinicians, and representatives of community advocacy groups. Some of the ideas are being tested in three cycles of mini-tests of modifications of the intervention.

For each cycle, eight young adults ages 18–26 seeking treatment for OUD at Mountain Manor participate in a refined version of the model for three months. The study team is tracking the number of medication doses participants receive, opioid relapse, days of opioid use, HIV risk behaviors, criminal behaviors, family member distress, and other measures.

The project’s first test-cycle variation is use of a mobile van for administering medications.

“The mobile van is well-suited to the current situation with the coronavirus pandemic,” Fishman said.

The pandemic is another barrier to treatment, because people are reluctant to go to clinics, and clinic staff worry about going into people’s homes due to the possible risk of exposure to the virus. The study team is modifying a van so that only the study participant and a nurse are involved in medication treatment. The van can be disinfected, and the air conditioning is kept running to ensure good circulation.

“Other tweaks we might test during the three cycles of the NIH HEAL Initiative project could include more frequent text messaging (even daily), video telehealth family sessions, more positive affirmations and good reports to families, transportation for study visits, and use of case management software,” Fishman said. “We will continue to ask for suggestions to improve.”

Once Fishman and his team have the results of the NIH HEAL Initiative project and have a better idea of what works, they’ll crystallize the refinements into a final system that they will test in a larger, 3-year randomized trial with 120 participants, to be funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This approach — optimizing the combined model prior to a costly, time-consuming larger trial — reduces some of the risks involved in the larger trial that could provide solid evidence of the effectiveness of the YORS model.

Looking ahead

The intervention has the potential to reduce barriers to treatment for young people who have OUD. Future research may focus on figuring out which components of the model are most meaningful and on tailoring treatment to meet individual needs.

If successful, the NIH HEAL Initiative project could set the stage for future work, including a cost analysis, a larger study at more sites for a longer time, and tests of less-intensive versions of the model. Such data could support wider use of the combined intervention approach, especially if healthcare costs associated with OUD are reduced by helping more people recover.

Read About This Project on NIH RePORT

Learn more about Fishman’s project, “The Youth Opioid Recovery Support (YORS) Intervention: An Assertive Community Treatment Model for Improving Medication Adherence in Young Adults with Opioid Use Disorder.”

Find More Projects in This Research Focus Area

Explore programs and funded projects within the Translation of Research to Practice for the Treatment of Opioid Addiction research focus area.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH)

Learn more about NCCIH’s role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services