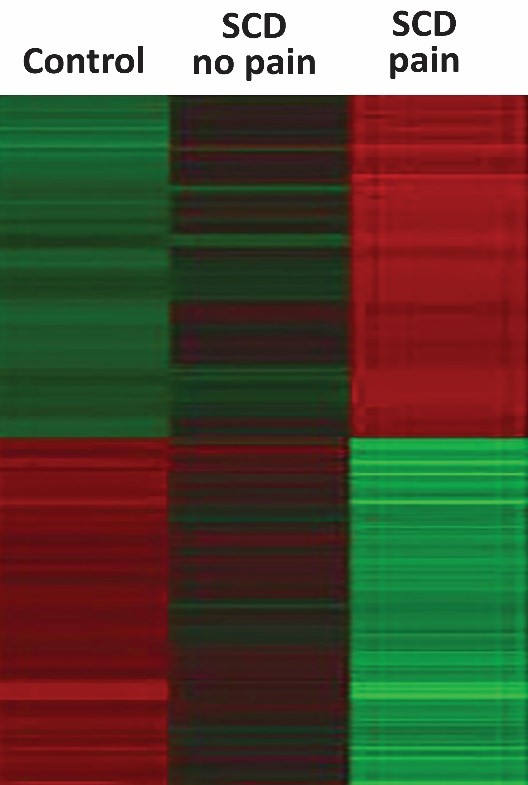

A new biosensing test measures the inflammatory index of patients with sickle cell disease who are in pain or not, as well as in patients without the disorder. Credit: Brandow and Panepinto team, Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee

Pain from sickle cell disease can be debilitating. People with this inherited condition often experience lifelong pain, coming in different forms and at unpredictable times.

About 100,000 people in the United States have the disease and it's more common in African Americans and Hispanics. These individuals have two defective copies of the gene for hemoglobin, the protein that routes oxygen through blood. As a result, their red blood cells look like crescent moons, or sickles. The misshapen cells are harder, stickier, and less effective at carrying oxygen compared to healthy red blood cells — causing pain, fatigue, and even strokes or organ damage.

Thanks in part to NIH research, a blood and bone marrow transplant is currently the only cure for some people who have sickle cell disease. But most patients do not have access to this treatment yet and need medicines and/or blood transfusions to manage complications, including pain. Opioids are very effective at providing short-term relief but don’t work well for chronic sickle cell pain that can linger for days, weeks, or sometimes even a month.

The Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative® is looking for novel ways to treat sickle cell pain that don’t involve opioid prescriptions. As part of the initiative’s research focus on finding specific, measurable characteristics called biomarkers, this research could lead to new types of effective pain medicines that don’t carry risk of addiction.

Many faces of sickle cell pain

In the 1900s, children born with sickle cell disease did not live to adulthood, but thanks to research advances, today the average life expectancy is 54 years. Managing pain is a top priority for people with sickle cell disease. Many children with the disorder have two or three painful flare-ups every year. This might feel like fingers that are on fire or legs that are being stabbed with giant needles. These episodes, called crises, send children, teens, and young adults with sickle cell disease to the hospital often.

Opioids work for some people with sickle cell disease, but not for others. A better understanding of the causes of this pain, and why it turns chronic, might lead to alternative ways to treat it.

“Understanding the pain that individuals with sickle cell disease experience is complicated,” says pain expert Amanda M. Brandow, D.O., M.S., of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. “We often don’t know exactly why patients feel pain. Why do some patients’ pain become chronic? And why do pain relievers help some people but not others?”

“In addition, because the experience of pain is so personal and ultimately best assessed by a patient, determining the impact of pain on a patient should include that patient’s self-report of pain,” adds Julie A. Panepinto, M.D., M.P.S.H., also at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and an expert in patient-reported outcomes. Brandow and Panepinto are part of NIH HEAL Initiative research to develop a new biosensor test to assess, in great detail, the “inflammatory index” of a patient’s immune system.

But this is no ordinary test that measures the levels of few chemicals at a time. It monitors the overall state of inflammation in an individual. This approach has helped predict why some individuals with a genetic predisposition to type 1 diabetes develop the disease while some do not. Brandow and Panepinto hope the biosensor test will help doctors identify and treat sickle cell disease pain.

Understanding inflammation

Inflammation is the immune system’s all-hands-on-deck reaction to injuries, like a stubbed toe, or invasions, such as infections. It also can be triggered by chronic diseases. During a typical immune response, battalions of white blood cells rush to hot spots in the body where they release an arsenal of chemicals — namely cytokines and chemokines — to contain and clean up the damage.

However, inflammation does not always operate like it is reacting to a five-alarm fire. The immune system can also deploy more moderate and long-lasting reactions.

“Years of research has shown that sickle cell disease is associated with high levels of chronic inflammation,” says Brandow. “We want to assess not only the state of inflammation in patients with sickle cell disease, but also how patients are regulating this inflammation.”

To do this, the research team plans to adopt a new type of test that requires a very small amount of blood. Originally developed by Martin J. Hessner, Ph.D., also of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, the test measures how components in a patient’s blood may trigger inflammatory gene activity in healthy white blood cells.

Beyond opioids

People with sickle cell disease may experience fatigue, shortness of breath, and swollen hands and feet. Some may experience a stroke, while others may go partially blind. However, their most common complaint is severe, debilitating pain.

For some children, sickle cell pain may start before they can walk, as early as six months of age. During childhood, the pain is usually acute, or short and intense, and often triggered when the misshapen, sticky red blood cells clog blood vessels. Doctors usually treat this type of pain with opioids.

“Opioids are very effective at treating acute pain. For most individuals with sickle cell disease, opioids provide a strong burst of relief for long enough for the pain to pass,” says Brandow.

But at least 30% of sickle cell patients may also experience longer bouts of chronic pain which occurs outside of, and in addition to, these acute pain events called vaso-occlusive crises. Scientists do not know exactly why some people with sickle cell disease experience chronic pain. Suspects include changes to the nervous system or problems with the immune system. But opioids are the go-to treatment regardless of its cause.

“The problem with using opioids for treating chronic pain is that they do not address the cause of the pain,” Panepinto explains. “Currently, we rely on external cues or patient reports to determine if a patient is experiencing pain and do not have a method to predict who is more likely to experience frequent pain crises during their lifetime. Getting a biochemical read-out of what’s going on inside a patient could be a big step to understanding their condition.”

Sensing inflammation

To assess a patient’s inflammatory index, the researchers take a sample of plasma (the yellowish liquid that immune cells swim in) from a patient’s blood and add it to healthy white blood cells sitting in petri dishes and let the cells sit and mingle for a few hours. This gives cells time to react to the inflammatory molecules swirling around in the plasma. The scientists then measure the gene activity inside the white blood cells to see which inflammatory chemicals were active at the very time the blood was drawn. The resulting biosensor paints a portrait of the patient’s inflammatory state.

Previously, Hessner’s team had shown that this approach was effective at predicting whether a person at risk of type 1 diabetes would develop the disease. It also helped identify which patients with type 1 diabetes and high inflammatory states should receive more personalized treatments to improve their conditions.

According to Brandow, blood tests are usually designed to directly measure the concentration of cytokines, but they can only detect a few molecules at a time. The biosensor test, on the other hand, allows researchers to simultaneously detect the presence of many cytokines from just a few drops of plasma.

“We’ve seen how effective it is in understanding type 1 diabetes and we hope we can do the same with sickle cell disease,” says Brandow.

The researchers plan to compare the results of the biosensor readouts with patient reports of their pain, which might help link pain perception with the unique inflammatory environment in an individual patient.

In preliminary studies, the team found that patients with sickle cell disease have a higher inflammatory index compared to patients without the disorder, and that the index is up when patients are in pain.

“Although we need to do many more experiments, this is a good first step,” says Brandow, adding that the biosensor may ultimately help researchers overcome hurdles to developing more effective, personalized treatments for relieving sickle cell pain.

Read About This Project on NIH RePORT

Learn more about Brandow’s and Panepinto’s project, “The Inflammatory Index as a Biomarker for Pain in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease”

Find More Projects in This Research Focus Area

Explore programs and funded projects within the Preclinical and Translational Research in Pain Management focus area.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

Learn more about NINDS’ role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services