What if you could start a medication today, and then forget about it for a whole year, while still receiving its health benefits? That’s the kind of technology that a California biotech company is developing to treat opioid addiction.

Like many diseases, opioid use disorder (OUD) can be treated successfully with medications. In the U.S., naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone are all approved for treating OUD and involve taking medicine every day or receiving a monthly injection. The challenge of taking these medications on a regular schedule can make adherence to treatment difficult for many people with opioid addiction. This puts patients at risk for relapse and overdose.

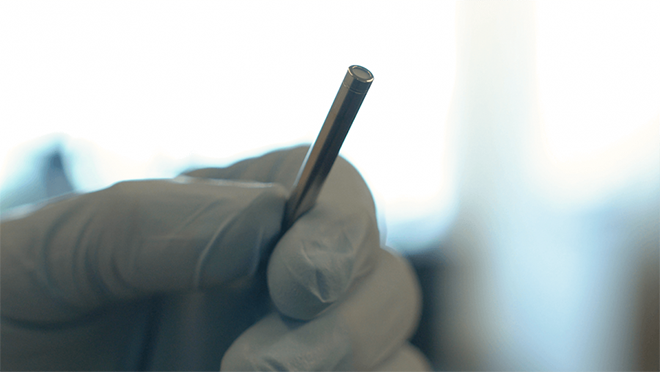

Delpor, a biotech company based in Brisbane, California, is using funding from the Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or the NIH HEAL Initiative®, to work on a technology that would provide a longer-lasting delivery system for naltrexone. The company is developing a titanium implant that goes under the skin, where it slowly and steadily releases medication into the body for a year. Delpor’s aim is to give patients more options and make it easier for them to stay on treatment long enough to achieve long-term recovery from the disease.

The NIH HEAL Initiative is taking on the opioid crisis from all angles, including by supporting research at private companies like Delpor that focus on making medication for addiction treatments easier for patients to use. Delpor’s grant is through the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Delpor is developing a titanium implant that goes under the skin, where it slowly and steadily releases medication for opioid use disorder for a year. Image courtesy of Delpor.

Naltrexone works by blocking the brain’s ability to respond to opioids. People using naltrexone who take an opioid-based drug won’t feel euphoria or other effects of opioids. Naltrexone is most effective when taken for six months or longer, but studies have found that only half of patients who start oral naltrexone remain in treatment six weeks later and only 15 percent are still on it after six months.1 Most patients who receive the injectable version do not return to their health care provider for a second shot.2

Delpor did not originally set out to treat OUD, says President and Chief Executive Officer Tassos Nicolaou. The company was formed about 10 years ago to develop an implant for an antipsychotic medication called risperidone to help people with schizophrenia stay in treatment.

“Patients do not always take their meds,” Nicolaou said. “Not necessarily because they don’t want to, but because the condition they’re suffering from affects their ability to follow a medication schedule, and they relapse.”

After a few years, Nicolaou and his colleagues wanted to expand to other medications. They needed options that would work with their implant. For example, a year’s supply of the medication must fit into an implant that is a little bigger than a matchstick. The company also wanted to focus on medications that people often stop taking. Naltrexone is one of a handful of drugs that the company is now studying for a possible implant.

Naltrexone is already Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved, which means that Delpor does not have to prove that the medication is safe. However, the company must show that the implant is safe and that it releases the medication steadily. The first set of tests, in animals, will provide data that the company will use for filing an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA within two years. If the FDA gives Delpor permission to proceed, the company will begin trials in humans to make sure that the implant performs as expected. If all goes smoothly, the implant could be submitted to the FDA for approval as soon as 2024. Once the FDA approves that application, the implant could go on the market.

That may sound like a long time, but it is remarkably fast for the process of developing a medical treatment. The funding from the NIH HEAL Initiative is helping make that timeline possible. Because only a handful of implants are on the market, private investors may be reluctant to take a chance on the research.

“For these types of futuristic products, it is difficult to find private funds,” Nicolaou says. Delpor has raised some private funding, but the NIH grant will enable the company to carry out animal testing and show that the implant can be manufactured consistently, he explained.

“There are people at the NIH who do have that vision,” Nicolaou says. “They want to think ahead, and we are so grateful to the NIH for the support that they have given us.”

The NIH HEAL Initiative is funding several other projects on alternative ways of delivering FDA-approved drugs for OUD, including projects on developing a naltrexone implant that dissolves under the skin, a version of methadone that is taken once a week rather than daily, and a naltrexone injection that would last two months rather than one.

An estimated 1.2 million people age 12 or older in the U.S. have OUD, according to the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 70,237 drug overdose deaths in 2017. Medication-assisted treatment for OUD is a lifesaving first-line therapy in the response to the opioid epidemic, and longer-acting medication options for patients are an unmet medical need that could increase adherence, sustain recovery, and save lives.

References

- Schuckit MA. Treatment of opioid use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):357–68.

- Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Leff JA, Linas BP, Walley AY. Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;85:90–96. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.001. Epub 2017 Jul 3.

Read About This Project on NIH RePORT

Learn more about Delpor’s project, “1-Year Sustained Release Naltrexone Implant for the Prevention of Relapse to Opioid Dependence.”

Find More Projects in This Research Focus Area

Explore research programs and funded projects within the Novel Medication Options for Opioid Use Disorder and Overdose research focus area.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

Learn more about NIDA’s role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services