Imagine you’re lying down on a hospital bed with a needle inserted in each side of your face. Every 20 seconds, you push a button to indicate how much pain you’re in. At first, you just feel a tingle, but then the pain builds. And builds. And builds.

That’s the experience of participating in a research project on pain by Alan Prossin, M.B.B.S., a psychiatrist and engineer at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Prossin works with healthy people who are scheduled to have plastic surgery and who volunteer to help him understand pain.

“They’re not so excited when they are experiencing the pain, but they’re happy to contribute to the science,” Prossin said.

Prossin’s work through the NIH Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, is part of the initiative’s research effort in discovery and validation of biomarkers for pain to create new, non-addictive treatments.

The connection between surgery and the opioid crisis

Many people first encounter opioids when the medicines are prescribed for pain after surgery. Most take opioids for only a short time, stop, and never have a problem. But for some people, those opioids lead to dependence or addiction. That’s why understanding pain and finding alternatives to opioid pain relievers are key goals of the NIH HEAL Initiative.

“One of the issues is that we don’t really have a personalized approach to dealing with pain,” said Prossin. A personalized approach to pain might include understanding how sensitive each person is to pain and whether non-opioid treatments might work better for them.

The challenge is that people vary in their sensitivity to pain. The same surgery might result in a lot of pain for one person and hardly any for another. Currently, doctors can’t know who will fall into which group. Prossin is developing new ways to predict which patients are most likely to experience pain after surgery, making it possible to tailor treatments.

Signing up for pain

To find a way to predict a person’s level of pain after surgery, Prossin first needs to induce pain in participants and measure their overall sensitivity to pain before surgery.

The whole procedure is done with the volunteer lying inside a machine called a PET scanner, which records brain activity. A needle trickles very salty water into the side of a participant’s face — and it hurts. During the test, Prossin increases the amount of water flowing through the needle. The higher the flow, the worse the pain.

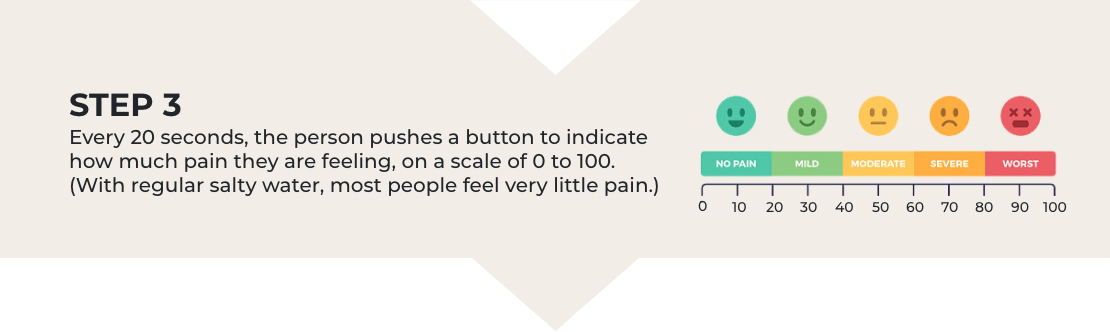

Prossin stops when a participant says their pain is about 40 on a scale of 0 to 100 — similar to a bad toothache. Participants who reach that level of pain at a lower flow of salty water are more sensitive to pain than those who stop only when the water flow is higher.

Prossin takes blood samples throughout the experiment. Along with the blood draws, the brain scans will help show how the body reacts to the painful procedure.

The Pain Sensitivity Test

These are the basic steps of the pain sensitivity test that participants in Prossin’s study will experience. Download a full-size version of this graphic. Graphic Credit: NIH HEAL Initiative.

Connecting proteins to pain

Prossin is looking at a group of proteins in the volunteers’ blood called the interleukin-1 (IL-1) family cytokines. The body produces these cytokines to help respond to infection and injury. Research on rodents has shown that higher levels of IL-1 family cytokines can make pain worse, and Prossin has data suggesting that the same is true for humans.

Later, after each person’s plastic surgery, the research team will monitor how much pain the volunteer feels — both in the short term and six to eight months later. Prossin will use this information to test whether cytokine levels from the first part of the study can predict how much pain someone experiences after surgery in both the short and long terms.

This knowledge might someday predict how likely someone is to experience pain after surgery. It could also help doctors use existing treatments in new ways, tailored to the individual patient. For example, one anesthesia medicine has been shown to reduce the levels of IL-1 family cytokines. Maybe, Prossin says, using that medicine in anesthesia for people who have high cytokine levels would lessen their pain after surgery. The hope is that such personalized approaches will improve patients’ experiences and, in the long run, result in fewer opioid prescriptions.

Research in its early stages

Prossin’s research is at an early stage; he is still recruiting volunteers for the project. He will also need to repeat the pain test in a larger group, including people with depression and anxiety — conditions that can make pain worse.

“I don’t want to say that I have the holy grail,” Prossin said. “I’m a realist. But I believe the work we are doing will contribute to the science. I hope it will bring us to a point where we can make treatment more personalized.”

Read About This Project on NIH RePORT

Learn more about Prossin’s project, “Discovery and Analytical Validation of Inflammatory Bio-Signatures of the Human Pain Experience.”

Find More Projects in This Research Focus Area

Explore programs and funded projects within the Preclinical and Translational Research in Pain Management focus area.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

Learn more about NINDS’ role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services