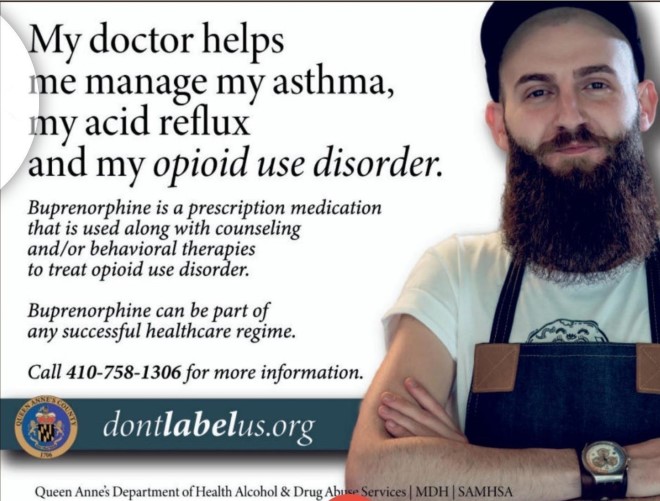

Don't Label Us is an effort from the Queen Anne's County Department of Health Alcohol & Drug Abuse Services, Maryland Department of Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Tess Henry and her mother, Patricia Mehrmann, have been in the news for years. Journalist Beth Macy chronicled Tess’s struggle to overcome a heroin addiction that started with an excessive prescription of opioids at an urgent care facility in 2012.

Until her murder in December of 2017, Tess was in a constant struggle to access one of the approved medication-based treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD) — methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone — all effective at helping people stop using opioids, stave off the painful withdrawal symptoms, and return to healthy living.

Methadone and buprenorphine are opioids themselves, but when prescribed by healthcare providers, they aid people’s recovery by preventing withdrawal symptoms and drug cravings, blocking the euphoric effects of opioids, and preventing overdose deaths. Naltrexone, which has no opioid-like effects, blocks the euphoric effects of opioids and reduces cravings.

But, although two million Americans are diagnosed with OUD every year and research shows that medication-based treatment for OUD works, many obstacles stand in the way of people staying on treatment. Only about a third of those diagnosed with OUD are treated with any of these medications. And getting access is only the first hurdle. Unfortunately, many people who receive these medications do not stay in treatment long enough to achieve long-term recovery.

Through the Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, NIH has funded the Optimizing Retention, Duration, and Discontinuation Strategies for Opioid Use Disorder Pharmacotherapy study to figure out how to best help people with OUD on their road to recovery.

That road can be long and hard.

“We’re asking individuals to voluntarily and permanently give up what they most desire [opioids] … with an athletic level of discipline, sustained determination, and without much training or experience,” says addiction researcher Hilary Connery, M.D., Ph.D., of McLean Hospital, a psychiatric hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts.

Connery’s McLean colleague Roger Weiss, M.D., along with John Rotrosen, M.D., of New York University, and Edward Nunes, M.D. of Columbia University, are leading the study.

It will test various doses, types, and lengths of treatment, toward understanding how to personalize therapy for people with OUD whose characteristics and circumstances can vary significantly. Addressing these differences is a key feature of precision medicine — treatment tailored to individuals — for any type of disorder: cancer, heart disease, depression, and so on.

The research will also try to answer a very difficult question about the length of treatment: Is it ever safe to come off medication-based treatment? If so, for whom and when is it safe, and what is the best approach to transitioning off medication?

“The stakes are high,” says Nunes, who routinely treats people with OUD, “because many people with OUD who stop their medication will relapse, and the risks of relapse include sudden death from opioid overdose.”

Right now, even for someone who has been doing well on medication, it’s unclear how to navigate this question, he adds, explaining why this research is so important.

“We don’t have the data we need to advise them: is it safe to stop?”

Navigating a successful journey

People with OUD can take medications for years, even for life. However, there are obstacles to staying on treatment long enough to achieve sustained recovery. Of those who begin medication-based treatment, only about half continue for as long as six months, and many of those who stop the treatment relapse and are at risk for opioid overdose and death.

Many barriers, including the addictive nature of opioids and the underlying conditions that might have led to their use in the first place – such as an acute or chronic pain condition or an undiagnosed or untreated mental illness – stand in the way of seeking and receiving medication-based treatment. It can be expensive and not covered by insurance. It’s not always available in many places where it’s most needed like the emergency department or in community-based treatment programs, and its availability is highly variable across the United States, especially in low-income rural areas. Stigma also remains a major reason for the dramatic underuse of medication-based treatment.

Life-changing questions

After months of treatment and counseling, which can help people with OUD stay in treatment, a patient might feel good, more confident, ready to try to stop the medication. They may also be scared, as they know of others who had tried and failed or had died of overdoses.

For various personal reasons, some people want to stop taking medication-based treatment, especially if they have been taking it for a long time and are doing well. The research will also address this issue — whether and under what circumstances it might be safe to stop. The researchers emphasize that they will warn people who choose to discontinue medication treatment that the choice is risky.

The research will test various approaches to gradually decrease treatment doses and will assess the value of a research-based mobile app that can give personalized care (motivating videos and personalized messaging) at moments when help isn’t around.

Real-world research

As the opioid epidemic continues to take the lives of too many Americans — about 130 a day — the NIH HEAL Initiative is supporting research that will change the course of this major public health challenge. As part of the initiative’s focus on translating evidence into practice, this medication-based treatment study mimics real-world conditions that people with OUD encounter routinely.

The initiative is tapping into the longstanding National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN), now expanded dramatically to address the goals of the NIH HEAL Initiative. Research within the CTN is carried out in community-based treatment settings, so people seeking treatment in their communities can participate, and the findings will be applicable to broad populations affected by OUD.

The research will occur at 18 sites across the country, and participants will be assigned at random to the different treatment conditions, which will assess multiple doses or forms of medications and application (app)-based interventions, in addition to usual counseling. It will test whether higher doses of sublingual buprenorphine, or a long-acting injection of buprenorphine, are more effective in keeping people with OUD in treatment.

The researchers will also assess the value of other types of support such as mobile apps that provide a mix of counseling and rewards for healthy behaviors. These apps, such as reSET-0, are already commercially available as digital therapeutics and have been shown to work under a healthcare provider’s supervision and in conjunction with medication.

What should patients do? What should the doctor advise? What should they know about the best way to achieve long-term recovery?

These are the questions HEAL seeks to address, but one thing is clear – achieving sustained recovery depends on multiple factors, with or without medication. Although everyone is unique in their journey to recovery, such factors include personal characteristics that shape an individual’s ability to handle the stresses of coming off medication and dealing with life’s inevitable ups and downs

The research will provide evidence for the best approaches to guide people on a successful path to recovery, on their own terms. “People need to be happy in their lives and have support when they need it,” says Weiss. “It’s a journey that can end well.”

Read about This Project

Learn more about the Optimizing Retention, Duration, and Discontinuation Strategies for Opioid Use Disorder Pharmacotherapy study.

Find More Projects in This Research Focus Area

Explore programs and funded projects within the New Strategies to Prevent and Treat Opioid Addiction research focus area.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

Learn more about NIDA’s role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services